(Longish note: I struggle with whether to include content warnings on my development posts. This post is largely about gun violence, including suicide. Suicide is something that can make me upset if I came across it unawares, so it’s something my instinctive reaction is to warn about. But for other people, other types of unpleasant content might be upsetting, and I’m not going to be able to know what all these things are or exhaustively tag them. So for now I will take the tactic of tagging any content central to the piece, but I will not provide explicit content warnings. I am thus warning my readers that things under the “development” category might have upsetting content beyond what is tagged. Alternative suggestions welcome.)

Before reading this post, it’ll be helpful to read the post it’s engaging with. “The Reductive Seduction of Other People’s Problems” is a development criticism article by Courtney Martin at BRIGHT magazine. It’s an accessible article that should be required for anyone from a rich country going into development.

To summarize Martin’s article:

Idealistic 22-year-olds with no skills from the US/Europe/etc going to low- or middle-income countries are not going to solve these countries’ problems, even if they at first think they are easy to solve. This “easy to solve” attitude is naïve and paternalistic: the situation behind why malaria isn’t eradicated/some people don’t have toilets/ government is corrupt is much more complicated than it seems from out-of-context. There are plenty of problems at home, a context you understand better. If you do want to make a difference in a place completely different from your home, you’d better be willing to stay long-term.

As a hypocritical, idealistic 22-year-old with no skills from the US who came to Zambia for a (relatively) short-term job, I agree with this.

However, in the past few months as I’ve been despairing about ever doing anything useful, I’ve had some interesting conversations with people who believe outsiders can add unique insight into local problems. While it definitely doesn’t apply in every case, their points have merit.

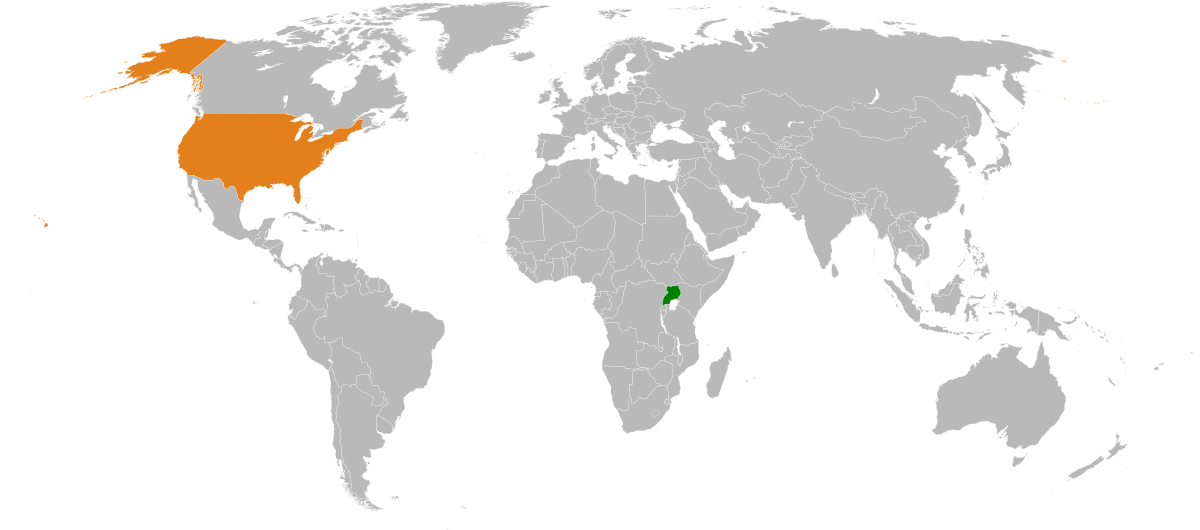

We can illustrate the potential value of outsiders by continuing the BRIGHT article’s framing parable of the Ugandan gun control advocate.

The framing story is about a hypothetical 22-year-old Ugandan who wants to come to the US wanting to solve school shootings because, he thinks, it’s such an easy problem to solve. But after talking to an American, it is implied, he realizes that there’s a bunch of cultural and political issues he needs to fight and solving school shootings would be the work of more than one lifetime. His idealism is gone. Martin uses this to argue that Americans/others from high-income countries are making the same naïve assumptions and proposing the same simple solutions about problems abroad, particularly in Africa, and it’s not good. And I agree!

It is vital to understand context and foolish to think you will easily solve the problems of a place you know nothing about.

But as someone who has done some research into gun violence, my other thought was this:

An idealistic 22-year-old Ugandan might come to the United States and do something useful about gun violence precisely because he is an outsider.

Here’s how it might go:

Before he goes, he thinks he’ll be a hero who stops school shootings forever, and quite easily. But when he arrives he realizes, as the BRIGHT article says, that there are complex systems that would make solving school shootings the work of a lifetime. He begins to despair and realizes he’s been naïve.

But during his doomed fight against school shootings, he’s been looking at data on gun deaths in the USA. He doesn’t have the baggage of seeing gun control as only a homicide issue (as many of us Americans do), but wants to decrease gun violence in America in whatever way he can. While school shootings are a problem, he finds that a vastly larger issue in terms of scale is suicide, particularly the suicides of middle-aged white men. In fact, twice as many Americans die by gun suicide every year than die by gun homicide. He finds how much limiting access to guns is predicted to decrease these suicides, and he sees, somewhat strangely, that this most at-risk demographic of gun suicides is least likely to support gun control.

The young man from Uganda is well aware that democracies electing dubious leaders and enacting dubious policies is a global trait, not a specifically American one. Thus, after doing some field research, he sees Americans who like guns and Donald Trump (and Americans who hate guns and Donald Trump) as normal people with imperfect information and cultural biases, not a special kind of evil unworthy of care. He realizes these people might be the most important targets and primary beneficiaries of gun control advocacy, but that there is a distinct lack of outreach to them.

He is Christian, like the average American. He grew up with parents who passionately preached against violence, which is what inspired him to work on reducing school shootings. He doesn’t think that ridiculing prayer is a good tactic to get those most at risk of gun violence to support stricter gun laws, and after talking to a bunch of Americans hypothesizes this is emblematic of a broader cultural divide and tension between two American tribes. So seeing that the pressure tactics and media coverage around school shootings aren’t working to squash gun violence, and feeling compassion for these people who are dying by gun suicide in such large numbers, he decides to start a nonprofit that aims to reduce gun suicides by using religious messaging to speak to middle-aged conservative men and their families…

(This is where my imagination ends. I am American and still too entrenched in my liberal culture to know exactly how such a nonprofit would function or if it would really be a good idea (which in my serious opinion, is why we need some Ugandans working on US gun violence). If anyone reads this, thinks this framing of the problem is useful, and has ideas, let me know).

Of course his nonprofit is not going to solve gun violence in the United States. But he may well reduce suicides, change the perspectives of a number of people, and change some local laws, precisely because as an outsider he was able to implement a new and creative way to deal with the problem.

I was so fascinated with the BRIGHT article’s framing story because it took me becoming a quasi-outsider to look at US gun violence in a different way.

The disproportionate number of gun suicides was something I didn’t know before leaving the US.

Far removed from Facebook posts and protests, I was reading about US gun issues in Zambia. I became more pro-gun control than I was before coming to Zambia because of what I found about suicide (mostly middle-aged white men in terms of numbers, although the rate is comparable among Native American/Alaska Native men), something I have legitimately never seen addressed on social media (and, somewhat bafflingly, is largely missing from either liberal or conservative media).

This does not mean no one is working on reducing gun suicides. This does not mean school shootings are not a problem. It just means suicides are a blind spot many gun control activists in the US have—ironically, treating them solely as a mental health and not a gun access issue—and that turning a fresh eye onto the current liberal narrative might be useful to enact change.

Again, I agree with the critiques of development in the BRIGHT article. I absolutely agree this Ugandan man will have the most impact if he decides to spend the next 20 years in the US, speaking to people at risk of gun suicide, poring over data (and advocating for better research to be done), understanding the NRA and US politics, making sure Americans are an integral part of the nonprofit’s staff, and so on. But even at that point, the perspectives he gained as a pastors’ child in Uganda, and as an outsider more generally, will be useful.

This illustrates why I do not hope for a parochial world. I hope for a world where people, from wherever in the world, can come together with humility to help solve each other’s problems.

I hope for a world in which a Ugandan can help stem US gun violence because he is data-driven and open-minded; a world where a Zambian can transplant her community’s concept of restorative justice to Louisiana’s prisons.

I don’t think idealistic people going to completely different places to try to solve problems is necessarily a problem: outsiders can bring much-needed perspective, free from the things that bias us against our countrypeople and cause us to look at problems in only one way. A 22-year-old Ugandan may be able to have impact on gun violence in ways an American liberal like me could never have.

The problem rightly noted by the BRIGHT article is that this exchange is mostly only happening in one direction, and often in unproductive ways involving the objectification and even exploitation of the people it is purporting to help.

For every New Zealander fighting corruption in a middle-income country, there are probably five New Zealand secondary school students spending $3000 on a trip to that country to shoddily construct some houses and take some exploitative pictures with kids.

I hope this estimate is overly pessimistic, but who knows? I am definitely not personally having the impact in Zambia that the hypothetical Ugandan gun control advocate has in my story. But I would like to believe my American-founded organization and others are doing something useful by using randomized control trials, begun for medicine in now-rich countries, to measure the effectiveness of development programs.

We’ll continue to discuss this in later weeks. Here I just wanted to provide a continuation of an interesting story, some food for thought, and some hopefully thought-provoking statistics and ideas about gun violence.

Tons of respect for this; well conceived and written. These are tough thoughts to communicate to non “development workers,” but you come through clear and accessible here.

Thanks Siobhan. I agree that an outsider will have trouble when trying to fix another country’s problems because the outsider does not understand the context well, but that simultaneously the outsider will bring a new perspective could lead to new, creative solutions. I also think there are some other good reasons for someone from a developed country to work on problems in a developing country. Since I read this post I’ve been trying to formalize what these reasons are, and I hope to keep thinking about them. What do you think of these?

*Good reasons to work on problems in a developing country if you are from a developed country*

1) You will bring a fresh perspective simply by virtue of being from a different place. This could lead to new, creative approaches to solving the problem. This is the point you make. As you say as well, this also works the other way, since it is additionally a reason for someone from a developing country to work on problems in a developed country. What’s more, it is also a reason for someone from one developed country to work on the problems of another developed country, or for someone from one developing country to work on the problems of another developing country (e.g., Bangladesh and Burundi – those are very different places)! This is also related to why it is good to have Britons studying US history or Koreans studying European society, etc.

2) You have a passion for the problems of one or more developing countries. Working on something you are passionate about often means you’ll be happier and do better work. So if you are passionate about clean water in South Asia, might as well work on it! I suppose it would make sense to ask yourself *why* you are passionate about it – you don’t want to go into it simply because the problem should easily be solved or you’ll be a Tindr Humanitarian – but it’s hard to know where passions come from sometimes, and often its best if we just follow them.

3) You’ll be helping someone very different from yourself. Sure, you could help the poor or suffering in your own nation too, and some of them will be very different from you. That is great too, but there is a different value in paying attention to the poor and suffering of those who are separated from you by nationality. I think the extreme case in which developed nations ignore the problems of developing nations entirely would be bad (though I admit that it is possible that the West has caused more problems in places like Africa and India, and these places would have been better off left alone, leading to my next point…)

4) Your country has already been involved in the history of developing countries and won’t be going away any time soon. You have a stake. This is particularly true for the US, which gets involved in everything. When I learned about post-colonial African history I was surprised to see how large of a role the US played, whereas I’d never heard of our involvement in places like Angola and Kenya. And when I was in Nairobi I saw the big US embassy and all the other foreigners’ presences. … Ok I’m not quite sure exactly why this is a good reason to work on issues in developing countries. Am I saying that the US caused these problems and so Americans should help fix them? Maybe. But that isn’t quite what I’m getting at. Or maybe instead it is a sense that Americans *will* be in Kenya, etc., so might as well make the contribution more positive? This is a point that doesn’t quite make sense yet but I think there is something there.

5) You have skills that are relatively rare in developing countries. Yes, there are also many skills you probably don’t have (like knowledge of agriculture or local languages) but you might know how to do statistics or program computers, or might have a good understanding of findings in academic research. There are always going to be some people in every country that have these skills, but since educational opportunities are worse in developing nations it means places like the West will have more of these people. We’d be lacking lots of knowledge about deworming, for instance, if Americans hadn’t written papers on it.

6) You will be working on the biggest problems. I’m of course not *sure* that these are the biggest problems, but the case to be made is that it really sucks to live in extreme poverty and a billion people do it. From a utilitarian perspective if you could get rid of any problem in the world, that’d be the one!

I’m curious to know which of these you agree or disagree with, and if this stimulates any new thoughts for you.

Hi Peter,

Thanks for the thoughtful comment. A lot of things to think about! I definitely agree with 1), which is why I wrote the post about it. My organization is trying to become a truly global one (I have colleagues here from all over Africa and Asia, as well as Americans), which is great! I also generally agree with 5). It would probably be good for development if more STEM people with hard skills, from wherever, began working in development – programmers and engineers are the most obvious.

I don’t have many coherent thoughts on 2), but if a problem like clean water in South Asia really is your life’s passion, you’ll probably be willing to put in a lot of time and effort learning local languages, moving there for good, etc (or if you do end up in a lab somewhere, you’ll end up being 5)). But maybe not! It’s not clear to me it’s a good reason unless it’s accompanied by other virtues (that I do not readily possess), like willingness to sacrifice comfort for years.

6) is important! (and 3) is also related I think; it’s good to be aware of other peoples’ problems and try to work on them, but that doesn’t necessitate development work). But, 6) could just as easily be an argument for going into finance and donating all your money to GiveWell’s top charities – or Zambian-run Zambian nonprofits. Or a myriad of other things. Two things I am interested in are domestic agriculture subsidies in rich countries (and food dumping), and labour migration and remittances (I will hopefully get around to writing posts on them). Americans inside the US could have more impact on these issues than Americans outside of the US. Someone who manages to stop US ag subsidies or expand labour migration, would IMO have much more impact on the world’s biggest problems than any development worker. As a more legit economist than me, you might have other thoughts on how to look at the world’s biggest problems outside of going there.

My previous paragraph also relates to 4). I’m not sure I completely understand your framing, but I think there is still much to be undone, ways rich countries are still messing up poor countries with their policies. It’s not immediately clear what these are, but they do seem to be structural and thus not necessarily addressed by traditional development work. Ha-Joon Chang in Bad Samaritans argues poor countries need more protectionism. Lant Pritchett in Let Their People Come argues for short-term labour migration. So again, not completely clear that being “on the ground” in development is what will right America’s wrongs. Maybe it is even better to expand your US business to Nairobi. But I don’t know – I would again love to hear your thoughts.

In short, I agree with each of these points to some extent. But traditional development work in a low-income country isn’t necessarily the best answer to them. And I don’t know what is.

Thanks for the reply Siobhan. I agree with you on all of this. Your point that there are other ways to work to improve the lives of low-income people in developing countries besides doing something that involves living in a developing country (“traditional development work”) is important. As you say, you could work on other problems for pay and then convert that pay into other people’s work on global poverty (through research funding or scaling up programs that are likely to be effective) – that’s earn-to-give. Or you could advocate for government policy changes in the US. There are still other things you could do without leaving home: you could develop technology that would be useful in developing countries, or you could research on neglected tropical diseases, or you could develop economic theories to improve our understanding of things like labor migration policies and agricultural subsidies.

Still, for any of these things to work, *someone* must be fairly confident how your efforts will effect the lives of people on the ground in developing countries. It wouldn’t be a good idea to pay for deworming if someone hadn’t tried it in Kenya and found that it was quite helpful. It wouldn’t do any good to end agricultural subsidies to US farmers if in fact these subsidies weren’t hurting farmers in Africa. To an extent you can get to these conclusions without spending time among the people who have these problems, but only to an extent. Someone has to see the final part of the picture.

Now, perhaps what would be best would be locals doing the legwork to determine what the root problems are and what, in general, the solutions should be, then only engaging outsiders for help with particular problems and for funding. This would mean Americans wouldn’t run non-profits based in Zambia. Only Zambians would. The Zambian non-profit might contract with Americans to develop products or get American funding, but everything would be run by Zambians. Americans wouldn’t be PIs on NSF-funded research projects. Zambians would be the PIs (though the US government could help fund them). And Zambia wouldn’t have to be overseen by World Bank technocrats in order to get loans or grants – the World Bank would simply provide what Zambia asked for.

If we get to a world where non-Zambians won’t add anything by leading non-profits or research projects or working as consultants on the ground, then an “only Zambian-run NGOs and projects” rule would be fine. But as it stands, I don’t think most Zambians would want such a rule in place. If a foreigner has a decent idea and the drive to carry it out, it’d be a waste to prevent them from doing that. This is of course contingent on a bunch of things we’ve already discussed, especially that you your idea is actually decent. Probably lots of failed development programs stem from overconfidence in what works on the part of foreigners.

So I think among Westerners working on problems in developing countries you have a mix. Some foreigners have good ideas and the passion to carry them out, so that what they are doing is a better use of time and money than if they were following locals’ explicit instructions or being a part of a local-run organization. But there are also other people who would have used their time and effort better by putting it more directly at the service of a local-run organization or project, but who were overconfident in their own plans, or who were there because their government, company, or NGO didn’t trust locals to identify and solve their own problems. It’ll be important that I continue to reflect on whether or not I’m in the first group…

This relates to a broader discussion about how economists should conceive of their practical work. Esther Duflo said in her AEA keynote speech in early 2017 that economists should be plumbers – they are told there are problems that they can help solve, then they tinker over time to make the system work (http://www.nber.org/papers/w23213). One economist at Harvard, though, when I asked him about the economist-as-plumber metaphor, said he didn’t really like it, since it assumed that people basically knew that their problems were and that economists shouldn’t go looking for deeper issues on their own. I think that’s a reasonable point, and I’m pretty confident Duflo would qualify her views in order to leave space for more creative work by economists. But on the other hand, the extreme view where you don’t listen at all to what the people you want to help think their problems are is also bad, and certainly plumbing sounds better than the one-size-fits-all thinking that (people say) characterized the Washington Consensus folks (who, I hear, failed).

This all would apply to someone who wants to help me with my problems, too. I might say “my problem is X” but some economist or psychologist or doctor could take a look at my life and see things I didn’t see, and say “actually your problem is Y, here’s how to fix it.” I don’t care if that person is American or not. If there’s an expert Nepalese doctor who can fix problems I didn’t know I had, that’d be great. Of course I wouldn’t want someone from Wakanda telling me what my problems were and ignoring her ignorance because she was from a more technologically advanced nation, just like a Nigerian doesn’t want an overconfident American lecturing him on his problems.

I don’t think I’ve disagreed with anything you said in what I’ve written here. I suppose I’ve been trying to work out when a foreigner would be more helpful working independently (though always in conversation with locals) than working directly for a local-run organization.